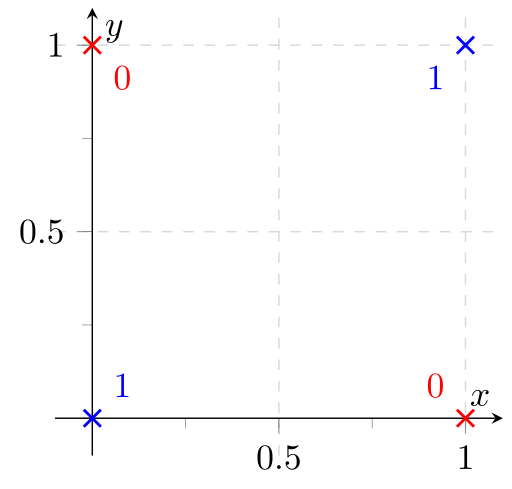

The XOR-Problem is a classification problem, where you only have four data points with two features. The training set and the test set are exactly the same in this problem. So the interesting question is only if the model is able to find a decision boundary which classifies all four points correctly.

Neural Network basics

I think of neural networks as a construction kit for functions. The basic building block - called a "neuron" - is usually visualized like this:

It gets a variable number of inputx $x_0, x_1, \dots, x_n$, they get multiplied with weights $w_0, w_1, \dots, w_n$, summed and a function $\varphi$ is applied to it. The weights is what you want to "fine tune" to make it actually work. When you have more of those neurons, you visualize it like this:

In this example, it is only one output and 5 inputs, but it could be any number. The number of inputs and outputs is usually defined by your problem, the intermediate is to allow it to fit more exact to what you need (which comes with some other implications).

Now you have some structure of the function set, you need to find weights which work. This is where backpropagation3 comes into play. The idea is the following: You took functions ($\varphi$) which were differentiable and combined them in a way which makes sure the complete function is differentiable. Then you apply an error function (e.g. the euclidean distance of the output to the desired output, Cross-Entropy) which is also differentiable. Meaning you have a completely differentiable function. Now you see the weights as variables and the data as given parameters of a HUGE function. You can differentiate (calculate the gradient) and go from your random weights "a step" in the direction where the error gets lower. This adjusts your weights. Then you repeat this steepest descent step and hopefully end up some time with a good function.

For two weights, this awesome image by Alec Radford visualizes how different algorithms based on gradient descent find a minimum (Source with even more of those):

So think of back propagation as a shortsighted hiker trying to find the lowest point on the error surface: He only sees what is directly in front of him. As he makes progress, he adjusts the direction in which he goes.

Targets and Error function

First of all, you should think about how your targets look like. For classification problems, one usually takes as many output neurons as one has classes. Then the softmax function is applied.1 The softmax function makes sure that the output of every single neuron is in $[0, 1]$ and the sum of all outputs is exactly $1$. This means the output can be interpreted as a probability distribution over all classes.

Now you have to adjust your targets. It is likely that you only have a list of labels, where the $i$-th element in the list is the label for the $i$-th element in your feature list $X$ (or the $i$-th row in your feature matrix $X$). But the tools need a target value which fits to the error function. The usual error function for classification problems is cross entropy (CE). When you have a list of $n$ features $x$, the target $t$ and a classifier $clf$, then you calculate the cross entropy loss for this single sample by:

$$CE(x, t) = - \sum_{i=1}^n \left (t^{(i)} \log \left ({clf(x)}^{(i)} \right ) \right)$$

Now we need a target value for each single neuron for every sample $x$. We get those by so called one hot encoding: The $k$ classes all have their own neuron. If a sample $x$ is of class $i$, then the $i$-th neuron should give $1$ and all others should give $0$.2

sklearn provides a very useful OneHotEncoder class. You first have to fit

it on your labels (e.g. just give it all of them). In the next step you can

transform a list of labels to an array of one-hot encoded targets:

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""Mini-demo how the one hot encoder works."""

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

import numpy as np

# The most intuitive way to label a dataset "X"

# (list of features, where X[i] are the features for a datapoint i)

# is to have a flat list "labels" where labels[i] is the label for datapoint i.

labels = [0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1]

# The OneHotEncoder transforms those labels to something our models can

# work with

enc = OneHotEncoder()

def trans_for_ohe(labels):

"""Transform a flat list of labels to what one hot encoder needs."""

return np.array(labels).reshape(len(labels), -1)

labels_r = trans_for_ohe(labels)

# The encoder has to know how many classes there are and what their names are.

enc.fit(labels_r)

# Now you can transform

print(enc.transform(trans_for_ohe([0, 1])).toarray().tolist())

Install Tensorflow

The documentation about the installation makes a VERY good impression. Better than anything I can write in a few minutes, so ... RTFM 😜

For Linux systems with CUDA and without root privileges, you can install it with:

$ pip install https://storage.googleapis.com/tensorflow/linux/gpu/tensorflow-0.5.0-cp27-none-linux_x86_64.whl --user

But remember you have to set the environment variable LD_LIBRARY_PATH and

CUDA_HOME. For many configurations, adding the following lines to your

.bashrc will work:

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH="$LD_LIBRARY_PATH:/usr/local/cuda/lib64"

export CUDA_HOME=/usr/local/cuda

I currently (19.07.2016) to use Tensorflow rc0.7 (installation instructions) with CUDA 7.5 (installation instructions). I had a couple of problems with other versions (e.g. #3342, #2810, #2034, but that might only have been bad luck. Who knows.).

Tensorflow basics

Tensorflow helps you to define the neural network in a symbolic way. This means you do not explicitly tell the computer what to compute to inference with the neural network, but you tell it how the data flow works. This symbolic representation of the computation can then be used to automatically caluclate the derivates. This is awesome! So you don't have to make this your own. But keep it in mind that it is only symbolic as this makes a few things more complicated and different from what you might be used to.

Tensorflow has placeholders and variables. Placeholders are the things in which you later put your input. This is your features and your targets, but might be also include more. Variables are the things the optimizer calculates.

Now you should be able to understand the following code which solves the XOR problem. It defines a neural network with two input neurons, 2 neurons in a first hidden layer and 2 output neurons. All neurons have biases.

#!/usr/bin/env python

"""

Solve the XOR problem with Tensorflow.

The XOR problem is a two-class classification problem. You only have four

datapoints, all of which are given during training time. Each datapoint has

two features:

x o

o x

As you can see, the classifier has to learn a non-linear transformation of

the features to find a propper decision boundary.

"""

__author__ = "Martin Thoma"

__email__ = "[email protected]"

import tensorflow as tf

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

def trans_for_ohe(labels):

"""Transform a flat list of labels to what one hot encoder needs."""

return np.array(labels).reshape(len(labels), -1)

def analyze_classifier(sess, i, w1, b1, w2, b2, XOR_X, XOR_T):

"""Visualize the classification."""

print("\nEpoch %i" % i)

print(

"Hypothesis %s" % sess.run(hypothesis, feed_dict={input_: XOR_X, target: XOR_T})

)

print("w1=%s" % sess.run(w1))

print("b1=%s" % sess.run(b1))

print("w2=%s" % sess.run(w2))

print("b2=%s" % sess.run(b2))

print(

"cost (ce)=%s"

% sess.run(cross_entropy, feed_dict={input_: XOR_X, target: XOR_T})

)

# Visualize classification boundary

xs = np.linspace(-5, 5)

ys = np.linspace(-5, 5)

pred_classes = []

for x in xs:

for y in ys:

pred_class = sess.run(hypothesis, feed_dict={input_: [[x, y]]})

pred_classes.append((x, y, pred_class.argmax()))

xs_p, ys_p = [], []

xs_n, ys_n = [], []

for x, y, c in pred_classes:

if c == 0:

xs_n.append(x)

ys_n.append(y)

else:

xs_p.append(x)

ys_p.append(y)

plt.plot(xs_p, ys_p, "ro", xs_n, ys_n, "bo")

plt.show()

# The training data

XOR_X = [[0, 0], [0, 1], [1, 0], [1, 1]] # Features

XOR_Y = [0, 1, 1, 0] # Class labels

assert len(XOR_X) == len(XOR_Y) # sanity check

# Transform labels to targets

enc = OneHotEncoder()

enc.fit(trans_for_ohe(XOR_Y))

XOR_T = enc.transform(trans_for_ohe(XOR_Y)).toarray()

# The network

nb_classes = 2

input_ = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=[None, len(XOR_X[0])], name="input")

target = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=[None, nb_classes], name="output")

nb_hidden_nodes = 2

# enc = tf.one_hot([0, 1], 2)

w1 = tf.Variable(

tf.random_uniform([2, nb_hidden_nodes], -1, 1, seed=0), name="Weights1"

)

w2 = tf.Variable(

tf.random_uniform([nb_hidden_nodes, nb_classes], -1, 1, seed=0), name="Weights2"

)

b1 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([nb_hidden_nodes]), name="Biases1")

b2 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([nb_classes]), name="Biases2")

activation2 = tf.sigmoid(tf.matmul(input_, w1) + b1)

hypothesis = tf.nn.softmax(tf.matmul(activation2, w2) + b2)

cross_entropy = -tf.reduce_sum(target * tf.log(hypothesis))

train_step = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.1).minimize(cross_entropy)

# Start training

init = tf.initialize_all_variables()

with tf.Session() as sess:

sess.run(init)

for i in range(20001):

sess.run(train_step, feed_dict={input_: XOR_X, target: XOR_T})

if i % 10000 == 0:

analyze_classifier(sess, i, w1, b1, w2, b2, XOR_X, XOR_T)

The output is:

Epoch 0

Hypothesis [[ 0.48712057 0.51287943]

[ 0.3380821 0.66191792]

[ 0.65063184 0.34936813]

[ 0.50317246 0.4968276 ]]

w1=[[-0.79593647 0.93947881]

[ 0.68854761 -0.89423609]]

b1=[-0.00733338 0.00893857]

w2=[[-0.79084051 0.93289936]

[ 0.69278169 -0.8986907 ]]

b2=[ 0.00394399 -0.00394398]

cost (ce)=2.87031

Epoch 10000

Hypothesis [[ 0.99773693 0.00226305]

[ 0.00290442 0.99709558]

[ 0.00295531 0.99704474]

[ 0.99804318 0.00195681]]

w1=[[-6.62694693 7.5230279 ]

[ 6.91208076 -7.39292192]]

b1=[ 3.32245016 3.76204181]

w2=[[ 6.63465023 -6.49259233]

[ 6.40471792 -6.61061859]]

b2=[-9.65064621 9.65065193]

cost (ce)=0.0100926

Epoch 20000

Hypothesis [[ 9.98954773e-01 1.04520109e-03]

[ 1.35455502e-03 9.98645484e-01]

[ 1.37042452e-03 9.98629570e-01]

[ 9.99092221e-01 9.07782756e-04]]

w1=[[-7.04857063 7.84673214]

[ 7.33061123 -7.68837786]]

b1=[ 3.53246188 3.89587545]

w2=[[ 7.35948515 -7.21742725]

[ 7.14059925 -7.34649038]]

b2=[-10.74944687 10.74944115]

cost (ce)=0.00468077

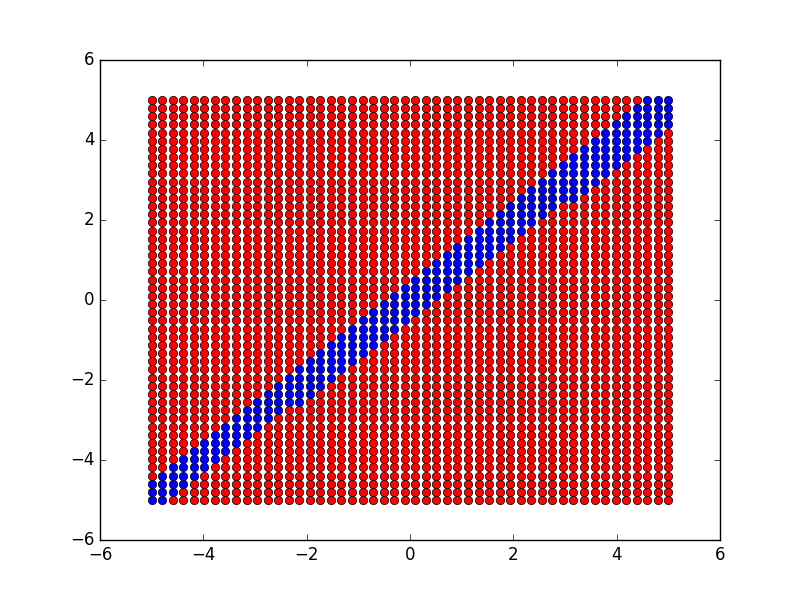

The resulting decision boundary looks like this:

I recommend reading the Tensorflow Whitepaper if you want to understand Tensorflow better.

Footnotes

-

Softmax is similar to the sigmoid function, but with normalization. ↩

-

Actually, we don't want this. The probability of any class should never be exactly zero as this might cause problems later. It might get very very small, but should never be 0. ↩

-

Backpropagation is only a clever implementation of gradient descent. It belongs to the bigger class of iterative descent algorithms. ↩